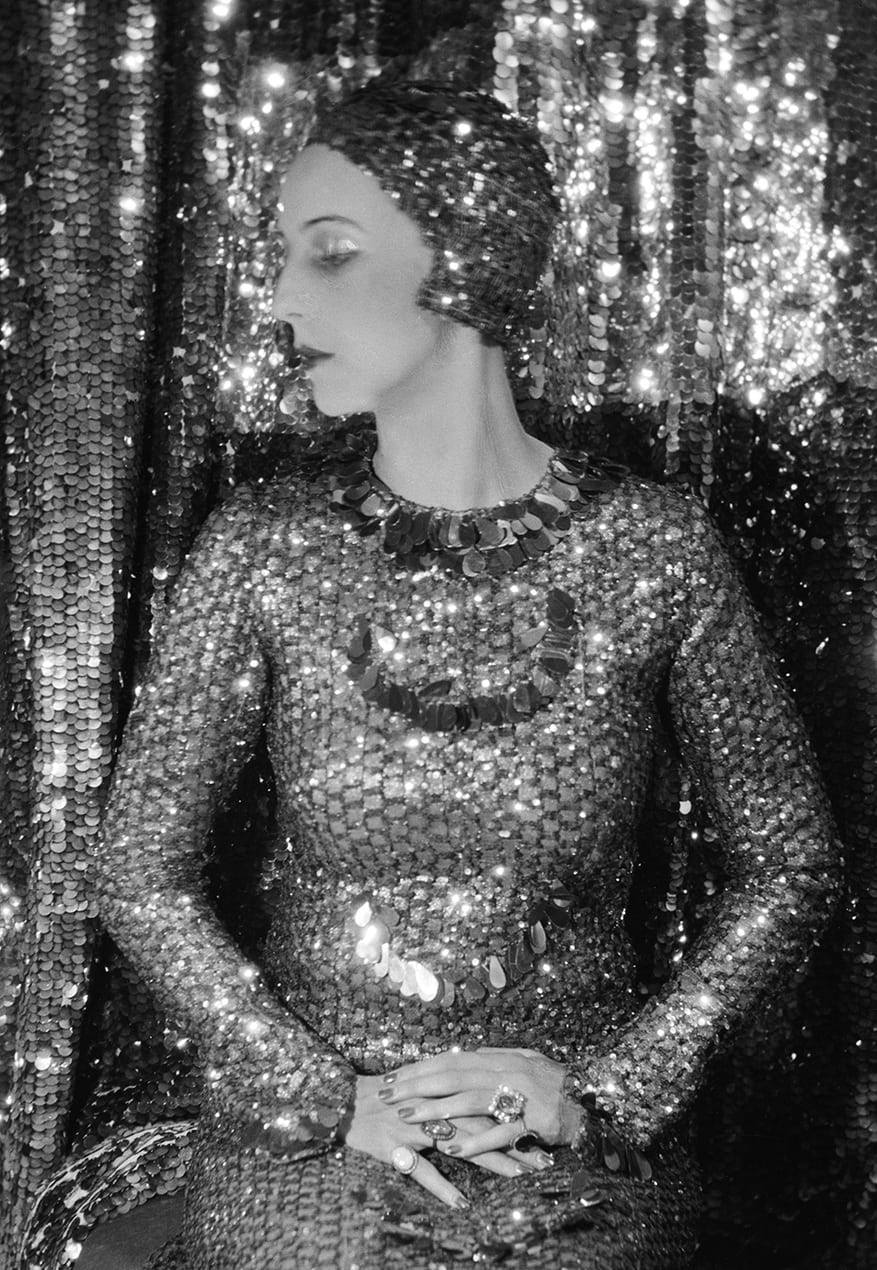

Bringing together a selection of rarely exhibited images that put the spotlight on the decadent extravagance of the 1920s and 1930s, The National Portrait Gallery’s latest show celebrates the golden age hedonism of Cecil Beaton’s ‘Bright Young Things.’ Here, the show’s curator Robin Muir talks us through some of the vintage treasures on display.

“The photographs that you’ll see in this show are all about surface sheen, glitter and silver,” reveals Robin Muir, curator of Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things. “There is no pretence to realism. Cecil turns [his sitters] into icons of beauty.”

This major show brings together around 150 works, many of which have been rarely exhibited, to explore the heady golden age of the ‘Bright Young Things’ – London’s stylish society set of the 1920s and 30s – through the lens of renowned photographer Cecil Beaton.

“We decided to focus on Cecil’s formative years because it’s a very interesting period in his development,” explains Muir. “He’s really wondering what he can do for photography and, just as importantly, what this new form of art can do for him.”

Pin

PinCecil Beaton was born in Hampstead in 1904 to middle class parents. He got his first camera, a Kodak Box Brownie, at the age of 11, but soon upgraded to the Kodak 3A Folding camera. With the assistance of his nanny, Ninnie Collard, Cecil photographed his mother and sisters styled in the manner of Hollywood starlets. “It was a difficult camera for an amateur to use,” explains Muir. “So, he took photos in earnest and learned by trial and error.”

It was, of course, Beaton’s magical mastery of the camera that expedited his escape from what he considered a fairly dull upbringing, explains Muir: “He sees in the pages of his mother’s weekly magazines this extraordinary world of gilded youth, a world that he desperately wants to break into. He thinks it will be very difficult, as he’s not moneyed or aristocratic, but what he quickly realises – as does his direct contemporary Evelyn Waugh – that if you have a particular talent that pleases people that is your entrée.”

Beaton certainly pleased his society sitters. “He took the most beautiful photographs of people,” adds Muir. “He pleases them and is warmly welcomed into their world.”

Pin

PinIt’s the deliriously eccentric world of the ‘Bright Young Things’ that Muir hopes to spotlight. The exhibition opens in 1924, the year that Cecil’s portrait of his friend George Rylands as ‘The Duchess of Malfi’ is published in British Vogue; and closes in 1937, the year of Cecil’s fabled fête champêtre at Ashcombe, his Wiltshire country home.

“It was a huge theatrical production with amazing decorations: Salvador Dali even helped with the masks for the waiters,” remarks Muir. “For me, it brings down the curtain on the ‘Bright Young Things’ era. It was one of the last great hurrahs before the storm clouds started to gather.”

Pin

PinOn display alongside dazzling portraits of artists and friends Rex Whistler and Stephen Tennant, set and costume designer Oliver Messel and glamorous socialites Edwina Mountbatten and Diana Guinness, will hang those of lesser-known personalities including modernist poet Brian Howard, Lady Diana Cooper, and Dorothy ‘Dolly’ Wilde, Oscar Wilde’s equally flamboyant niece.

“Dolly is one of my favourites,” Muir concedes of the portraits on display. “She was celebrated for simply being a sparkling conversationalist.” Further probing, though, unveils a tragic fate: the socialite died of a probable drug overdose in 1941. It seems Dolly was not alone. “A lot of people didn’t survive this period of hectic hedonism,” adds the curator. “hope when visitors see the captions, they will delve further into the backstory of some of the people.”

Pin

PinIt took the curatorial team four years to track down the wealth of mesmerising prints on display. Treasures include a rare vintage print of leading ‘Bright Young Things’ dressed as 18th-century shepherds and shepherdesses and vintage prints of Beaton’s earliest subjects, his sisters Nancy and Baba.

“We tried very hard not to show modern black and white blow-ups,” says Muir. “We wanted to find the original print that Cecil would have made for himself or given to a sitter to give people a sense of history. These are lucky survivors, relics of the past.”

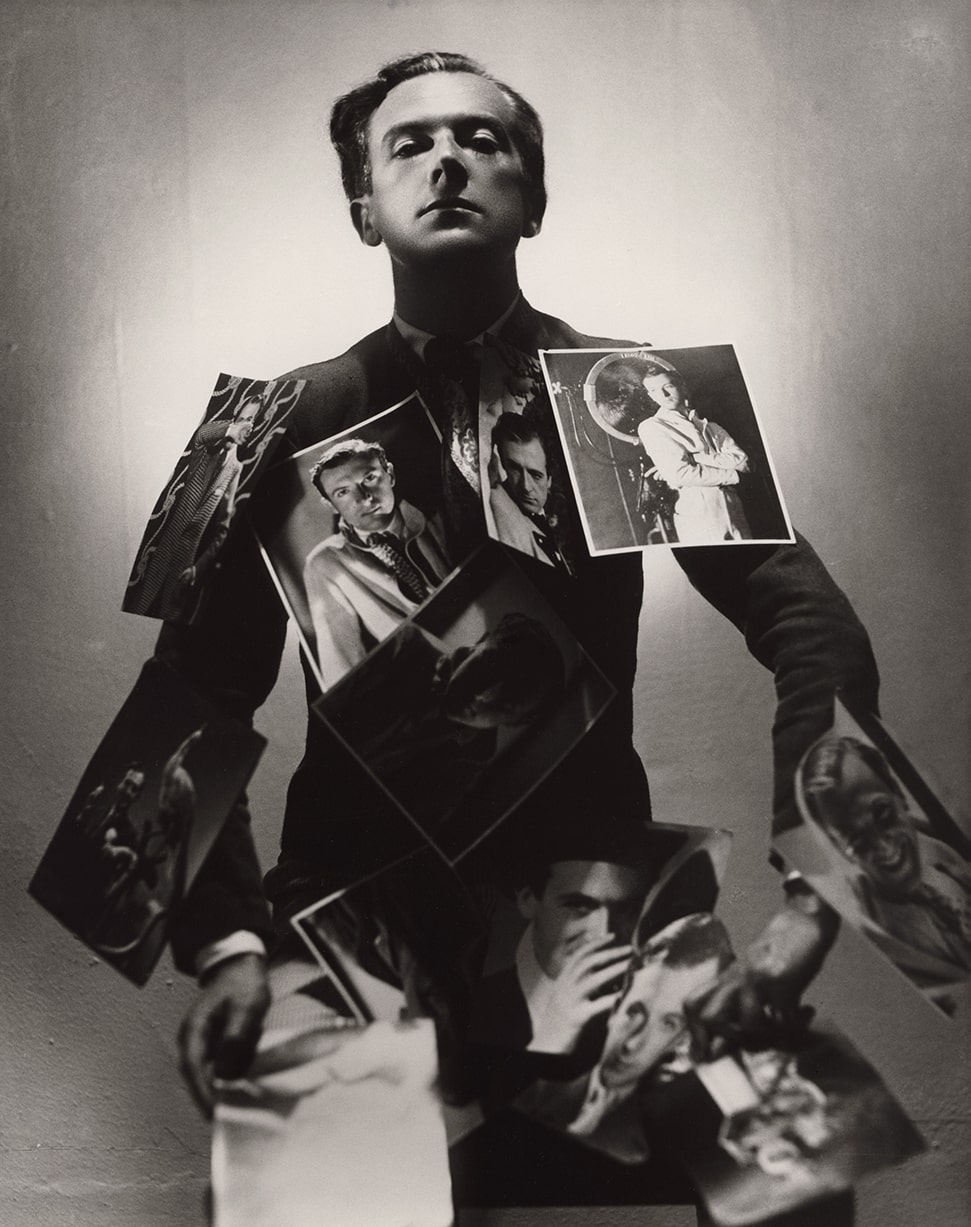

Pin

PinThe show will also spotlight a group of works featuring Cecil, a much-photographed celebrity in his own right, by his contemporaries. The striking 1937 portrait of Beaton by the photographer Paul Tanqueray is one such example. “I wanted to bring in some works by people he knew very well and admired,” says Muir. “I also wanted to bring colour into the show; Cecil doesn’t take colour pictures until after the war.”

The outbreak of war triggered a seismic change in Beaton’s photographic style. By swapping society portraiture for war photography, Cecil was able to “shut the door on his Bright Young Things past and reinvent himself as a very serious photographer,” affirms Muir.

He also embraced set and costume design (for which he won three Oscars), wrote dozens of books and diarised prolifically. “I had always had this idea of Cecil as being ambitious, certainly, but very vain, self-aware and slightly amateurish,” reveals Muir. “But he was, in fact, extremely technically adept and an incredibly hard worker.”

Pin

PinWhat Cecil was able to achieve in 76 years was, as Muir puts it, “quite extraordinary”. Not only did he capture some of the greatest names of the 20th century, including Greta Garbo, David Hockney, Queen Elizabeth II and Marilyn Monroe, but he also elevated the status of photography.

“Even until the 50s, photography was often looked down on as an inferior trade,” explains Muir. “But Cecil transcends that. He is welcomed with shrieks of laughter and gaiety. He turned the photographic sitting into a joy.” Nearly a century on, it seems fitting to look back at the glittering faces that shaped Cecil’s trailblazing vision.

Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things

National Portrait Gallery, St Martin’s Place, Covent Garden, London, WC2H 0HE

www.npg.org.uk

Main image: The Bright Young Things at Wilsford by Cecil Beaton, 1927. © The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive